As our school has made the transition to a competency-based system, many educators I have spoken to over the past two years have asked me “What is different about your school now?” This million-dollar question is one that I had not thought a lot about as I was living the change, but began to realize the answer through sharing our work with others.

Over the past year, our school has had a number of national visitors, ranging from the Chief Council of State School Officers to the United States Education Department’s Ann Whelan and Emma Vadehra. As I have planned for, facilitated, and observed these visits, I began to realize exactly was different in Memorial School now as opposed to three to four years ago.

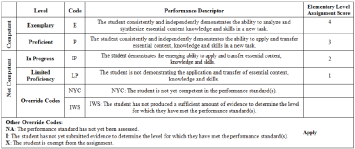

During any visit our school has, we make sure that we don’t do any anything “special”, that we aren’t pretending to be someone we aren’t. We have typically had students (usually fifth graders) share their experiences about their understanding and knowledge of how skills and dispositions play a major role in their overall understanding of themselves as learners. In a competency-based system, reporting of progress in both academics and behaviors is done in a pure fashion (meaning they are separated, so as not to muddy what the reported grade represents) , so students and teachers know exactly which competencies, academic and non-academic, students have mastered.

Additionally, we bring our visitors into a grade level to watch what we call LEAP (Learning for Each And every Person) to see our multi-tiered system of support in action. Providing and structuring these individualized opportunities for support or extension within the daily schedule is imperative in a competency-based model. Some have a very hard time visualizing what this might look like with five and six year-old students, so we tend to share Kindergarten LEAP, if it is occurring during the visit, so that we may demonstrate what it looks like to have an effective, differentiated structure of support and extension, even for our youngest learners.

These first few portions of the visit are what I would refer to as the “tip of the iceberg.” They are interesting, providing examples of many of the important characteristics of great instruction and assessment practices within the classroom, and are examples of a highly functioning PLC. But what comes next is hidden “under the surface”, but truly significant. It’s what visitors to our school end up remarking about after…

We typically end with a session providing time for our visitors to speak with and ask questions of those in our school who make everything happen-our teachers. Again, each visitor is coming with their own set of questions about what they would like to know, so we open it up immediately for them to ask anything they want.

And this is what I would refer to as the depth, or 2/3 of the iceberg beneath the surface of the water. Our teachers’ understanding of curriculum, instruction, and assessment practices has grown tenfold over the past four to five years. When our teachers discuss any of these topics, it becomes incredibly clear what the difference is in our school now as opposed to three to four years ago. Each teacher is able to passionately and clearly articulate their understanding of not only best instructional and assessment practices related to the leverage standards and competencies students must demonstrate mastery of, but also the details of where each and every student in their classroom and grade level (the benefit of highly functioning PLCs) is and what they are doing to allow them to continue along their learning progression.

This is where the true power of competency education becomes evident. What may look to be typical in an elementary classroom is truly much deeper than it may appear. Every center, conference, and activity is geared toward something greater, and students’ ownership and investment in their own learning is evident, as well.

Getting to a point in which teachers are this aware of not only their students’ areas of strength and need but also their own, takes time, focused professional development, and a collaborative culture intent on realizing the growth and learning for all within the environment. This awareness and true understanding of their craft is the depth and power of a competency-based educational system.

Jonathan Vander Els is the principal of Memorial School in Newton, NH. Jonathan has presented at multiple local, state and national conferences on topics related to competency-based education, enhancing teacher leaders in schools, maximizing collaboration of staff through highly functioning Professional Learning Communities, and providing tiered instruction for learners of varying abilities. Jonathan may be followed on Twitter: @jvanderels